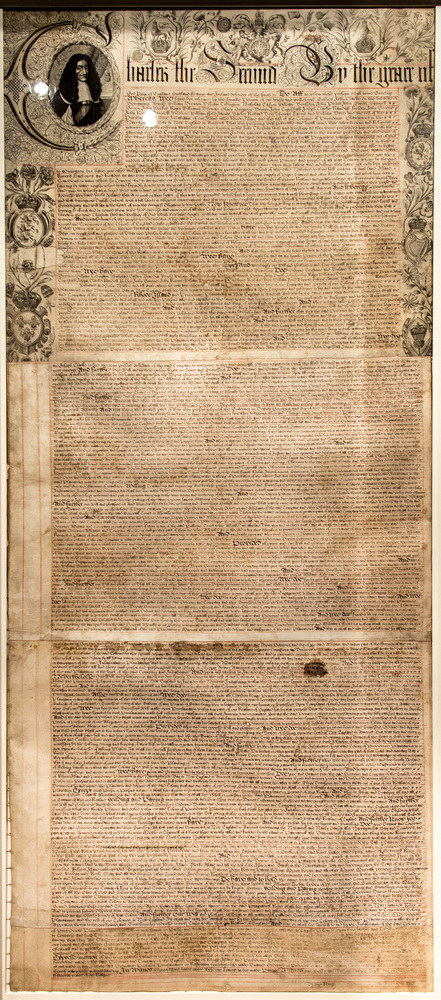

The Charter of Rhode Island

‘You may know that I am willing to encourage the hopeful undertaking of my said loyal and loving subjects. I will secure them in the free exercise of all their civil and religious rights. I will preserve unto them that liberty in the true Christian faith and worship of God, which they have sought to enjoy with so much travail.Some of the people of the colony cannot, in their private opinions, conform to the public exercise of religion, according to the liturgy and ceremonies of the Church of England or take or subscribe the oaths and articles made in that behalf. I hope that by reason of the remote distances of those places, there will be no breach of the unity and uniformity established in this nation. I do hereby declare that no person within the said colony at any time hereafter shall be in any way molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question for any differences in opinion in matters of religion, who does not actually disturb the civil peace of the said colony. All and every person may freely enjoy his and their own judgments and consciences in matters of religious concernments throughout the land, if they behave themselves peaceably and quietly, and not use this liberty to licentiousness and profaneness, nor to the civil injury or outward disturbance of others, any law, statute, or clause therein [contained in the rest of this Charter].’

In the 1620s a group of rigorous Protestants, called Puritans, settled in the region of Massachusetts (in North-east America). They intended to live according to their strict interpretation of Christianity and did not accept dissidence. Rhode Island, in contrast, was established by Roger Williams, also a devout Christian but one with some extraordinary radical ideas. Under his inspiration Rhode Island granted freedom of religion to all (see clipping on Rhode Island and Roger Williams). In 1663 King Charles II of England issued a Royal Charter for the Rhode Island colony. The Charter actually confirmed the practices that had been in place since the beginning following the principles of its main founder, Roger Williams. The colony was explicitly referred to as a ‘lively experiment' because of its democratic principles and the freedom of religion granted to its inhabitants. The King gave the colonists the civil and religious freedom they had requested, but he hoped that the colony’s ‘experiment’ would not affect people living in England (‘there will be no breach of the unity and uniformity established in this nation’). He declared that the colonists would not be punished for practicing different religions and were permitted to follow their own ‘judgements and consciences’ regarding religion.

For more information on this and other peace treaties, see

Title

content

I hope that by reason of the remote distances of those places, there will be no breach of the unity and uniformity established in this nation.

I do hereby declare that no person within the said colony at any time hereafter shall be in any way molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question for any differences in opinion in matters of religion, who does not actually disturb the civil peace of the said colony. All and every person may freely enjoy his and their own judgments and consciences in matters of religious concernments throughout the land, if they behave themselves peaceably and quietly, and not use this liberty to licentiousness and profaneness, nor to the civil injury or outward disturbance of others, any law, statute, or clause therein [contained in the rest of this Charter].’

Context

In 1663 King Charles II of England issued a Royal Charter for the Rhode Island colony. The Charter actually confirmed the practices that had been in place since the beginning following the principles of its main founder, Roger Williams. The colony was explicitly referred to as a ‘lively experiment' because of its democratic principles and the freedom of religion granted to its inhabitants.

The King gave the colonists the civil and religious freedom they had requested, but he hoped that the colony’s ‘experiment’ would not affect people living in England (‘there will be no breach of the unity and uniformity established in this nation’). He declared that the colonists would not be punished for practicing different religions and were permitted to follow their own ‘judgements and consciences’ regarding religion.